Scientists will set out this week to drill a hole into the Indian Ocean floor to try to get below the Earth's crust for the first time.

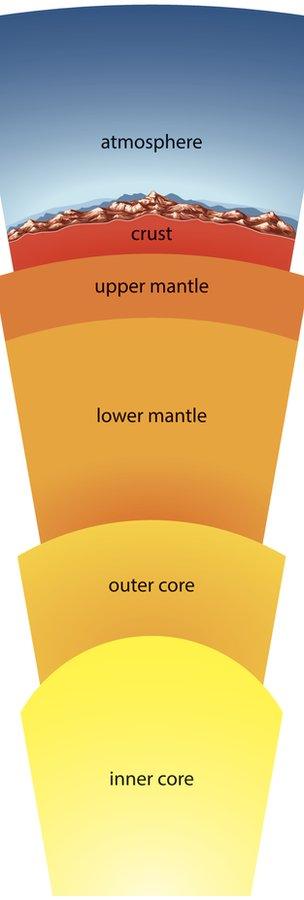

They want to sample rock from the planet's mantle - its deep interior.

In the process, the researchers hope to check their assumptions about the materials from which the crust itself is made.

It will probably take several years to drop the full 5 to 5.5km, says co-team leader, Prof Chris MacLeod.

Thinkstock

Thinkstock

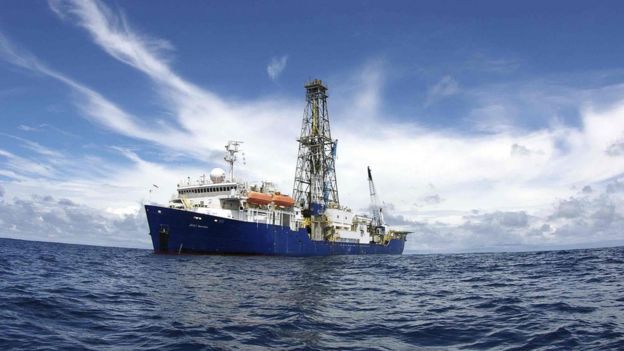

This is in addition to the 700m of water between the drilling ship, the Joides Resolution (JR), and the seabed.

"In total, we think it will take three expeditions," the Cardiff University geologist told BBC News.

"The science is approved and we have funding for this initial two-month investigation. But we will need to come back and we may not complete the task until the 2020s."

There have been several attempts to drill into the mantle, but none has yet succeeded.

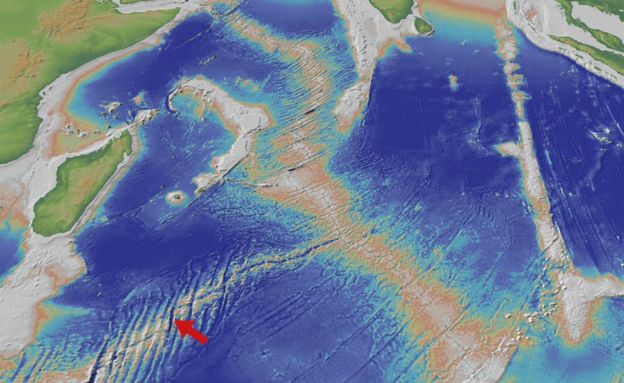

This latest effort may fare better, however, because faulting and erosion have already thinned the crust at the targeted drill site, known as Atlantis Bank on the South West Indian Ridge of the Indian Ocean.

The project, which is running under the auspices of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP), would give scientists access ultimately to fresh, unaltered peridotite - the rock, rich in olivine minerals, that, because of the size of the mantle, makes up the bulk material of the planet's interior.

This is a worthwhile goal in itself. But as they sink deeper and deeper, the researchers want also to test current models for how the crust is constructed and constituted.

In particular, Prof MacLeod is keen to probe the so-called Moho boundary.

This is the famous "discontinuity" where seismic waves from earthquakes abruptly change speed.

The textbook explanation is that the Moho draws the line between the crust and the mantle: a demarcation between familiar igneous surface rocks - such as granites, basalts and gabbros - and those of the interior peridotites.

But Prof MacLeod suspects the discontinuity could also describe in places the depth to which water has managed to penetrate into the peridotites to produce a different type of rock known as serpentinite.

CARDIFF UNIVERSITY

CARDIFF UNIVERSITY

Given that the seismic signature of this material is essentially the same as crustal igneous rocks, there is no way of telling - other than to drill and sample everything between the seabed and the top few hundred metres of unadulterated mantle.

If proven correct, the more sophisticated Moho description would have a number of far-reaching consequences for our understanding of how the planet is put together.

For a start, it would mean the igneous ocean crust is far more variable in thickness and in structure than previously recognised.

"The Moho is pretty uniform everywhere across the ocean basins, and because of that everyone has assumed that the ocean crust is very uniform and therefore, by inference, very simple," explained Prof MacLeod.

"But if we're right here, it changes the game completely. If the Moho seismic boundary is actually an alteration boundary from water penetration into the mantle, it means we know a lot less about the ocean crust than we did."

IODP

IODP

And it might also say something really quite profound about life on Earth, because the process of making serpentinites (serpentinisation) is a huge draw for microbes.

The hydrogen and methane produced as the peridotites' olivine minerals are altered in contact with water can be metabolised by single-celled organisms. If serpentinite is shown to be more extensive than current models accept, then it means assessments of the scale of the biology occurring inside the Earth has also been greatly underestimated.

"If there's far more serpentinite down there, goodness knows how much of it has microbes in it," said Prof MacLeod.

Tuesday sees the IODP Expedition 360 team board the Joides Resolution in Colombo, Sri Lanka. The ship should put to sea later this week.

Because Atlantis Bank has been drilled before, and its condition is known, fairly swift progress is expected on this first outing, with the hole being opened to a depth of perhaps 1.3km below the seabed.

Assuming all goes well, the next opportunity to drop the hole further still may come in 2018. This would be dependent on funding and of a capable ship like the JR being available.

No comments:

Post a Comment